Among the hallmarks of obstetrics, we find the demanding and mercilessly busy and exacting nature of a specialty which is also notorious for attracting medicolegal limelight. Patiently explaining and quantifying risks to patients along the legal requirements of complete disclosure may prove virtually insurmountable challenges to an exhausted practitioner seriously lacking sleep and possibly a decent meal while the pager relentlessly intrudes. However, the serious issue of full disclosure can no longer be relegated to second or third class priority in a discipline which lays much emphasis on operational skill and technological knowledge. It is becoming a crucially indispensable element in a wholesome obstetric practice seeking maximal legal protection. This article considers a number of obstetric disclosure issues including a re-evaluation of doctor-patient communication in modern obstetrics.

Keywords: Obstetric disclosure, litigation, communication, landmark case, will to discuss, contemporary guidelines, knowledge of the law.

Obstetrics is associated with ever increasing litigation with resultant rocketing of indemnity costs [1] and their attendant evils. One notes that in the period 1982-1986 a marked average jump of 10% in litigation cases occurred, particularly in obstetric cases [2], which at the time were greatly fuelled by the then recently introduced and much misinterpreted intrapartum cardiotocography. This article evaluates one of the multi-faceted contributing factors to modern obstetric litigation, namely disclosure. In truth, much of the discussion is applicable to all other disciplines and to the great majority of civilised countries where one practices. As expected however, the medico-legal framework often varies from country to country and sometimes from state to state in the same country. Although an Anglo-American viewpoint is maintained here, we write about principles which are universally applicable.

It is perhaps naïve not to expect a low threshold for litigation in a field where enthusiastic parents-to-be dream of the perfect child born in a perfect medical setting and with staff which shares their enthusiasm and provides individual attention. Anything less, especially in the presence of an adverse medical outcome, may jar deep-seated sentiments and initiate a psychological reaction which may eventually lead to litigation and Court action. Optimal communication is one of the best antidotes to this scenario although it does not replace good obstetric practice.

Even ideal obstetric practice without adequate communication and patient bonding may still leave dangerous room for dissatisfaction, especially during the highly emotionally charged period of labour. A patient’s bruised ego, be it justifiable or not at the most stressful time of labour may escalate matters in the case of an adverse clinical outcome [3]. This may even be based on misinterpretation of management facts which were never explained or discussed, even if briefly, to allow the patient to clear her mind. The Closed Case Database (which reflects the consumer’s viewpoint) massive content of minor problems is instructive. Among the commonest complaints found in the Closed Case-Database, we find much evidence of patients feeling ignored and mistreated [4].

Good communication, besides being an essential ingredient of the legally regarding disclosure, may correct wrong perception of mismanagement with its potential legal implications. Few situations may be worse than imparting the news of a stillbirth. Yet, it is an established fact that the way by which this catastrophe is imparted to the parents has a profound and lasting impact on them [5]. One may further state that any factor which diminishes good communication will exert a further multiplier effect on the delivery of disclosure to the patient and again, on the perception of this delivery by the patient.

Good communication and complete disclosure go hand in hand. In an atmosphere of good rapport fostered by adequate communication, imparting full disclosure is more likely to be received, assimilated and retained. Conversely, a negative or stressful ambience may lead to situations where disclosure will not only induce anxiety and negativity but may not even be assimilated at all. Severe stress has a negative effect on both the brain’s ability to encode information as well its later recall [6]. Park et al. have shown that information garnered just before shock induced stress by rats resulted in its amnesia [7].

Communication is crucial not only in disclosure but also in diagnosis and treatment. In Eldridge and Others v. Attorney General of British Columbia and Another (Attorney General of Canada and Others, intervening) [8], the Court clearly declared that effective communication is an integral part of medical care. Hence, it is clinically extremely relevant to consider causes of impaired communication which is the very basis of doctor-patient bonding. In litigationridden countries, lack of adequate communication is known to be a commoner cause than diagnostic errors in litigation issues [9]. Lack of communication has both direct potential litigatory implications and indirect ones, among which the ramifications into adequate disclosure.

One cause of impaired communication emanates from markedly unequal sociocultural backgrounds between patient and obstetric health giver. Thus, women with a non-western background are at an obstetric disadvantage, with impaired communication contributing negatively to their perinatal mortality by as much as 21.7% [10]. Language problems may be intrinsic to this scenario where doctorpatient bonding may also be exceptionally difficult and this itself contributes to potential litigation [11]. And to language problems one may add both physical impairment such as speech/hearing difficulties as well as psychological/psychiatric conditions impairing cognition as well as medications, alcohol and drugs of abuse.

Disclosure oriented litigation may also involve the medium of communication. Especially, but not limited to the effects of the Covid pandemic, virtual communication in some cases has become the order of the day. All communications impinging on the disclosure element, be they be by telephone, text message, emails, skype, zoom, etc. must be noted in the patient’s clinical file and may need explaining in Court. It may well be, for example, that a patient reverts by text message to the obstetrician to clear queries which arise a number of hours or even days after an explanation of the risks of an elective caesarean section. The upshot of this is the absolute need for all communication by whichever medium to be accurately dated and timed and be available for recall if and when necessary. This aspe3ct of disclosure is likely to increase in importance.

This 2015 United Kingdom High Court case brought to the fore the crucial importance of full disclosure by the obstetrician to effect a valid consent, rendering patient autonomy essentially unassailable. Up until then, defendant doctors in Court would invoke Bolam’s Law to defend disclosure issues under the umbrella of the doctor disclosing what the doctor thought best for the patient. Medical paternalism at its choicest! In Montgomery the facts of the case took this paternalistic attitude to a twisted extreme which clearly evidenced the obstetrician’s manipulating facts through lack of disclosure to effect a patient’s choice along the obstetrician’s wishes

The case involved a pregnancy in a diabetic, primigravid patient of short stature who was carrying a clinically large baby. The patient, herself, a PhD graduate, repeatedly expressed serious reservations about the safety of vaginal delivery to her obstetrician who brushed these concerns aside. In fact the obstetrician admitted in Court that had she offered the option of a caesarean section, the patient would have jumped to it! So, she refrained from discussing the existent 10% risk of shoulder dystocia, which complication did in fact ensue in labour with resultant severe cerebral palsy of the new-born child. The Court of Appeals ruled for the patient and rightly awarded her £5.25 million.

In effect, the trend favouring full patient disclosure had been in practice in the UK Courts and elsewhere such as USA, well before Montgomery. However, while Bolam’s law held sway since 1957 [13], doctors in Court could always claim they disclosed whatever they disclosed along what they believed were the patient’s needs. The Montgomery ruling delivered the judicial coup de grace to Bolam as regards disclosure. Following this landmark ruling any patient undergoing any medical or surgical treatment must be supplied with all the relevant information to enable an education choice or refusal of management. This also implies discussing all forms of any alternative treatment available, their indications, limitations, risks and associated pain and its management. If a particular line of management is being offered one must also explain the likely outcome if the suggested treatment is not accepted. All queries by the patient must be accommodated even if the doctor needs to research further and another session of discussion is required.

In situations where time is not a pressing problem, the obstetrician would do well to actually plan optimal disclosure. For example in the case of an elective CS, it might be advisable to discuss the situation a few weeks before the planned date of surgery. This will enable the patient to reflect and eventually ask whatever questions she must ask. It is imperative that such discussions are all noted in the clinical file. In particularly difficult situations or worrying patients, it would be advisable to disclose in front of a witness such as a nurse or midwife, whose name is included in the patient’s clinical file.

Good communication and full disclosure are in the clinician’s best interests quite apart from the required fulfilment of the law. Firstly, it fosters further doctorpatient bonding. Secondly and more importantly it tends to eliminate any possible misunderstandings by the patient. One example comes from ultra-sonography, where lack of adequate explanation of the necessary procedure has led to a number of Court claims alleging sexual assault with the use of vaginal ultrasound [14].

The modern obstetrician indeed like all clinicians of all medical specialties is no longer at a cross-roads of choice, but rather faces a one-way street where full disclosure is concerned. However, at this juncture it is incumbent to stress that a knowledge of relevant medical law is absolutely essential if one is to practice within safe legal boundaries. Instilling at least a basic working knowledge of medical law is an urgent academic necessity and we believe should commence at undergraduate level. The lack of knowledge of the law by most obstetricians and indeed by most medical doctors in general is often acknowledged widely. In a whitepaper on Legal Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Barbados, 52% of senior medical staff and 20% of senior nursing staff knew little of the law pertinent to their work [15]. We believe this to be a rather accurate universal truth.

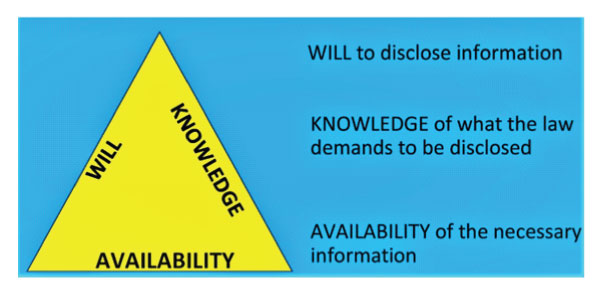

Effective disclosure in any clinical situation may be visually represented by a triangle showing the three crucial basic elements.

Firstly, there must be a will to disclose conscientiously and not just to pay lip service to a legal requirement. This may not be as easy as it sounds. There are patients who severely try one’s patience especially under challenging clinical/time pressure limits. The hard of hearing, the foreigner who speaks no English, the unaccompanied patient with low IQ, etc. are all sad cases which may not elicit the humanity they need. Even worse are situations with patients who are capriciously difficult. Such disclosures should definitely be witnessed and recorded.

Secondly the obstetrician must know the expectations of the law of disclosure. The law does not require arm-length lists but genuine conveyance of understanding to the patient of what is to be embarked upon. She is to be encouraged to discuss and query facts in a brief but complete explanation of facts. Rattling through a long list of complications will leave the patient stunned and not only unenlightened but wondering how to make the fastest exit. The obstetrician must use common sense and place oneself in the patient’s shoes. Rather than bland general complications the patient must be singled out with her own particular case, situation and circumstances.

Current guidelines stress that doctors should disclose the facts of treatment, the possible complications, possible alternative treatments and what will happen if the proposed treatment is not followed. Although a doctor must not exert pressure, a patient expects guidance rather than neutrality. Omitting a personal opinion, when one is specifically requested, after stating what is indicated and necessary, in certain circumstances may even constitute an abrogation of humane care within the art of healing [16]. Hence a wise clinical path must be considered. As long as the spirit of the obstetric advice is in the patient’s best interests, no obstetrician should be afraid of giving guidance when requested. This contrasts with the guilty defendant in the Montgomery case where information was withheld with a view to pushing the patient to a vaginal delivery.

And thirdly, the obstetrician must be in possession of the full and correct facts before imparting them to the patient. This demands that the obstetrician is not only au fait with contemporary obstetric management but is fully cognizant of the latest official guidelines of information pertinent to the particular situation in his particular hospital and obstetric unit. One example would be knowing the capabilities and limitations of the particular neonatal unit where the obstetrician will be delivering a premature baby. In a scenario where for example college delivery guidelines refer to an obstetric unit with standard contemporary requirements, an obstetrician working in a unit below par will be misleading the patient if such circumstances are not explained. For example, an obstetrician must be aware that the ACOG now recommends noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) as a first-line test before the classically taught first performance of PAPPA, free beta-HCG, etc.

The Courts are providing factual evidence of the price to pay for failing to abide by what is accepted practice and official teaching One may easily quote cases of proven liability resulting from failed disclosure. For example a contemporary case concerned a family physician who failed to inform his pregnant patient about the relationship between folic acid supplements and the prevention of neural tube defects, such as spina bifida. The judge ruled that there had been a wrongful act (negligent advice) leading to an occurrence (sexual intercourse in a folic acid deficient state) which resulted in a child born with disabilities due to that deficiency of folic acid [17].

The law expects the modern obstetrician to deal with patients along the concept of the prudent patient which includes respecting patient autonomy with regard to choice and acceptance of treatment which in turn demands full disclosure of facts. The prudent patient principle originated from the 972 USA case Canterbury v. Spence [18]. And it ushered in the very antithesis of the medical paternalistic attitude based on the maxim that doctor knows best. Subsequently championed in 2015 in Montgomery, the prudent patient principle is now essentially universal in most of the civilised world and hold that that it is the patient who decides his or her on management after being enlightened by his or her doctor.

Although this article cannot possibly delve into the myriad aspects of obstetric disclosure, its scope is to stress that modern obstetric practice must in all its aspects align itself with the patient’s will as enlightened by the necessary disclosure. It also emphasises that irrespective of clinical outcome, infringement of the laws of disclosure as they stand, constitute a serious breach of the patient’s rights.